The Birth of the Modern Shipping Container (1950s-1960s)

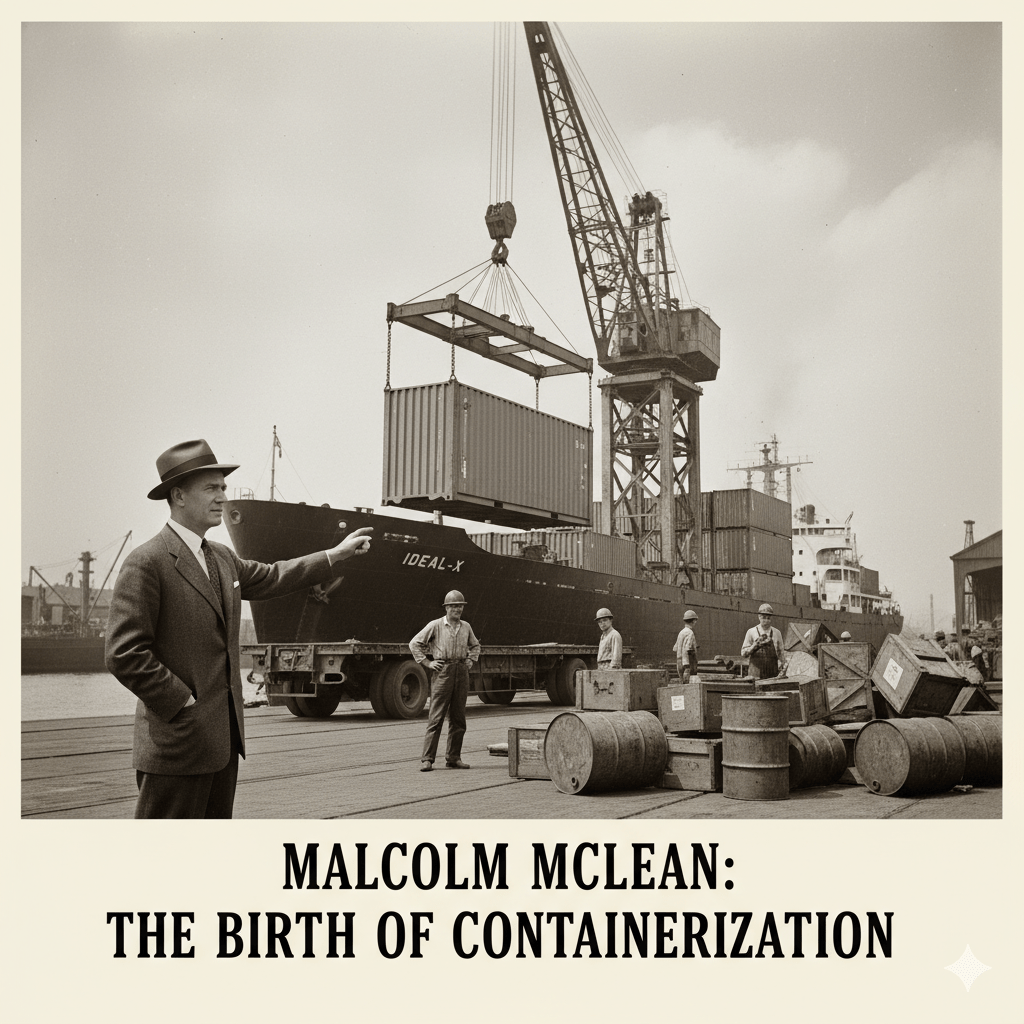

Malcolm McLean and the Invention of Containerization

Before the 1950s, cargo ships were loaded and unloaded by hand in a painstaking process called “break-bulk shipping.” Dockworkers would manually load individual items into nets, which cranes would then hoist aboard ships. This inefficient system often kept ships in port for weeks, with labor costs accounting for up to 70% of shipping expenses.

Enter Malcolm McLean, a North Carolina truck driver turned entrepreneur who revolutionized global shipping. McLean didn’t start in the shipping industry – he built one of America’s largest trucking companies after buying his first truck in 1934. His frustration grew from waiting at ports while longshoremen slowly unloaded his trucks and reloaded items onto ships.

In 1955, McLean sold his trucking company and purchased Pan-Atlantic Steamship Company (later renamed Sea-Land Service) to pursue a radical idea: what if entire truck trailers could be loaded directly onto ships? McLean refined this concept, realizing that just the trailer bodies – without wheels or chassis – would be more efficient to stack and secure.

On April 26, 1956, history was made when the converted WWII tanker Ideal X departed from Newark, New Jersey, carrying 58 metal containers bound for Houston, Texas. The maiden voyage of these pioneering containers reduced loading time from days to hours and slashed costs from $5.86 per ton to just $0.16 – a 96% reduction.

Early Standardization Challenges and the ISO Standards

Despite the clear advantages of containerization, early adoption faced significant hurdles. Throughout the late 1950s and early 1960s, shipping companies developed containers with wildly different dimensions, connection points, and structural specifications. This lack of standardization meant containers from one company often couldn’t be handled by another’s equipment.

The critical turning point came in 1961 when the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) began developing uniform standards for shipping containers. By 1968, they established specifications for container dimensions, corner fittings, identification markings, and testing requirements. These standards primarily focused on two sizes that remain dominant today: 20-foot and 40-foot lengths.

The standardized corner fittings were particularly revolutionary, creating universal connection points that worked with cranes, ships, trucks, and trains worldwide. This intermodal compatibility transformed containers from a company-specific solution into a global system.

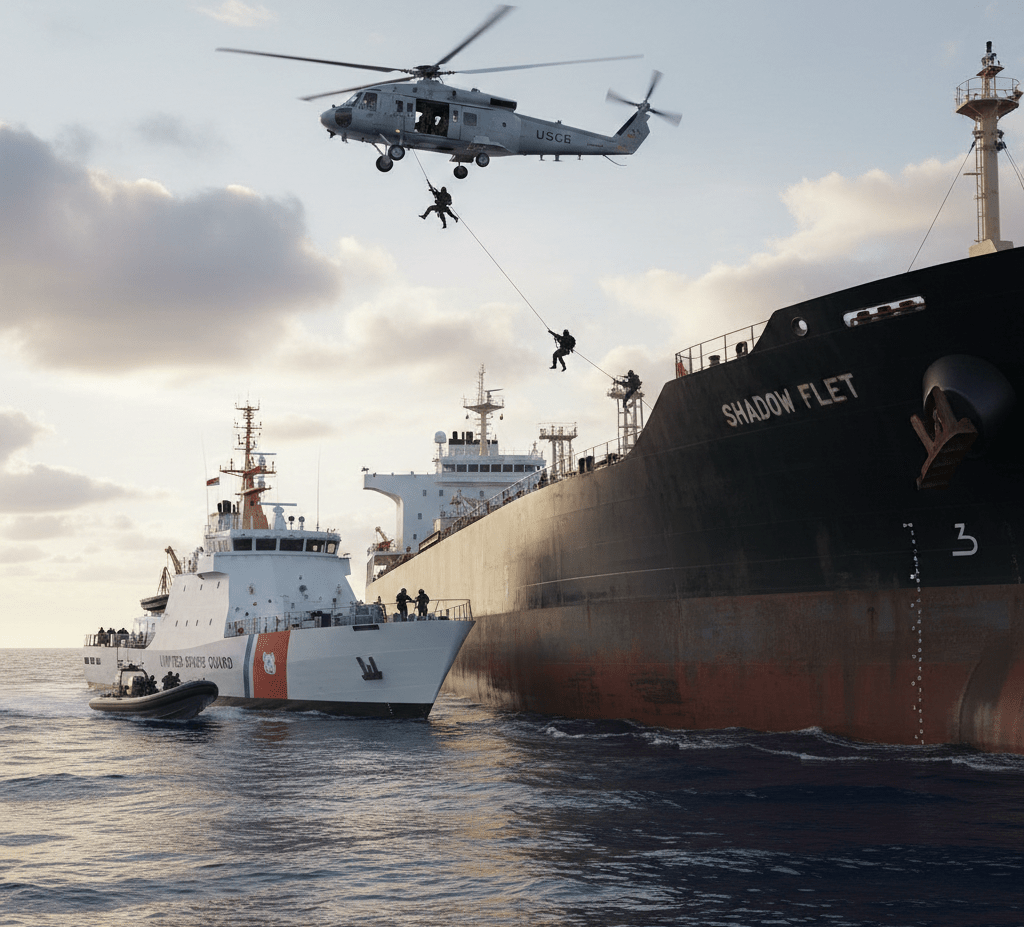

The Vietnam War’s Role in Containerization Adoption

The Vietnam War played a surprising but pivotal role in container shipping’s rapid growth. By the mid-1960s, the U.S. military faced enormous logistical challenges supplying forces in Southeast Asia. Traditional shipping methods resulted in massive port congestion, pilferage, and supply delays.

In 1967, the military embraced containerization, signing contracts with Sea-Land and other carriers to deliver supplies to Vietnam. Military logistics specialists quickly discovered that containerized cargo reduced theft, improved inventory tracking, and dramatically accelerated supply delivery to troops.

This military investment sparked a container infrastructure boom. Purpose-built container ships emerged, designed specifically for maximizing container capacity rather than retrofitting existing vessels. Specialized container ports developed in both the U.S. and Vietnam, featuring gantry cranes and storage yards optimized for rapid container handling.

By the war’s end, containerization had proven its superiority in even the most challenging environments, setting the stage for its explosive growth in commercial shipping throughout the 1970s and beyond.

The Global Economic Impact of Container Shipping (1970s-Present)

Revolution in Port Operations and Labor

The introduction of standardized shipping containers transformed port operations with unprecedented efficiency gains. Before containerization, loading and unloading a medium-sized cargo vessel required dozens of dockworkers and could take up to two weeks of grueling manual labor.

This dramatic reduction in turnaround time slashed shipping costs and port congestion. Ships once spent two-thirds of their operational life sitting in ports; with containers, this dropped to under one-third, allowing vessels to spend more time at sea generating revenue. The Economist has described this transformation as “the humble hero” of globalization, noting that a single modern container ship can now be loaded or unloaded in less than a day.

The human cost of this revolution was substantial. Dockworker communities that had thrived for generations faced massive workforce reductions. San Francisco’s waterfront alone saw employment plummet from 10,000 longshoremen to under 1,000. The shift from labor-intensive handling to mechanized operations triggered fierce labor disputes throughout the 1970s and 1980s across major ports worldwide.

In the UK, the National Dock Labour Scheme collapsed in 1989 after bitter strikes, while American dockworker unions negotiated automation agreements to secure better compensation and safety standards for remaining workers. The International Longshore and Warehouse Union eventually embraced technological changes in exchange for higher wages and job security guarantees for its smaller workforce.

The Container’s Role in Globalization and Supply Chain Management

The standardized shipping container didn’t just change ports—it remade the global economy. Transportation costs plummeted by approximately 90%, making once-prohibitive international trade routes economically viable. Products that would have been too expensive to ship internationally suddenly became profitable global commodities.

This cost reduction enabled manufacturers to establish production facilities wherever labor and resources were cheapest. As Harvard Business Review research shows, container shipping made just-in-time inventory systems feasible on a global scale. Companies could reliably order components from overseas suppliers with predictable delivery times, minimizing inventory costs.

The results were dramatic. Between 1970 and 2000, world trade grew at twice the rate of global GDP. Manufacturing hubs emerged across Asia, particularly in China, which became “the world’s factory.” Containerization enabled the outsourcing revolution, creating intricate supply chains spanning multiple countries, with products assembled from components manufactured on different continents.

Evolution of Container Ships and Megaports

Container ships have grown exponentially since their early days. The first purpose-built vessels in the 1960s carried just a few hundred TEUs (Twenty-foot Equivalent Units).

Today’s Ultra-Large Container Vessels (ULCVs) like the HMM Algeciras can transport over 24,000 TEUs—equivalent to a single train stretching 77 miles long. Marine Insight’s historical analysis tracks how these ships have continually broken size records, driving economies of scale.

This growth prompted massive infrastructure investments. Traditional ports couldn’t accommodate these behemoths, spurring the development of megaports with deep water berths, massive gantry cranes, and automated handling systems. Singapore, Shanghai, and Rotterdam transformed into logistics hubs processing millions of containers annually.

Strategic chokepoints gained renewed importance. The Panama Canal’s 2016 expansion accommodates vessels carrying up to 14,000 TEUs, while the Suez Canal’s 2015 expansion created a parallel channel to increase capacity—investments proving critical during supply chain disruptions like the 2021 Ever Given incident.

Environmental and Technological Innovations in Container Shipping

Despite their massive scale, modern container operations have achieved significant environmental improvements. Efficiency gains have reduced the carbon footprint per container moved by approximately 50% since the 1990s. Slow steaming practices—reducing vessel speeds—cut fuel consumption by up to 30%.

The digital revolution has reached shipping containers themselves. Smart containers equipped with IoT sensors now track location, temperature, humidity, and security status in real-time. This visibility allows for predictive maintenance and precise supply chain coordination.

McKinsey’s industry research highlights how shipping lines are experimenting with sustainable alternatives. Major carriers have invested in LNG-powered vessels, while others explore hydrogen, ammonia, and wind-assisted propulsion. Industry leaders have committed to carbon neutrality by 2050, aiming to transform one of globalization’s most essential yet emissions-intensive industries.

Leave a comment